With four-stroke, single-cylinder engines, a combustion is generated at every two rotations of the crankshaft. It's known as the "power phase". All other phases, like intake, compression and exhaust, are energy-consuming. The role of the flywheel is to store kinetic energy from the power phase and release it during the other phases. With multi-cylinder engines, the action of the flywheel is never felt.

|

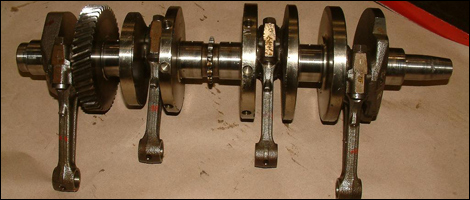

| Crankshaft of a four-stroke engine. |

Weight might pose a problem: the heavier a flywheel is, the lower the engine speed will be. That's why multi-cylinder engines use a smaller, lighter flywheel. Nowadays, with sportbikes reaching 15,000 rpm, the flywheel needs to be incredibly light. Since storage systems use magnetic fields and their magnets are integrated to the flywheel, they add weight to the latter. Over the last 10 years, though, the weight of magnets has considerably decreased thanks to new lightweight materials that can retain the same kind of magnetic field as a steel magnet.

On some high-performance bikes, the flywheel is even shorter in diameter and rotating twice as fast by way of a higher gear ratio. This maximizes engine speed and power.

In 1984, Suzuki introduced the GR650 powered by a single-cylinder engine which featured balancing weights offering the best of both worlds: good cyclical regularity and uncompromised performance under acceleration. The main flywheel relied on a secondary flywheel that was held in check by a jaw mechanism until the engine reached 2,500 rpm. Beyond that point, the centrifugal force opened the jaws and freed the flywheel.